view main Luna page >>

view updated profile of killer >>

Another drug prosecutor vanishes

on a Pennsylvania car rideMissing DA Gricar had days earlier announced arrests in

'largest heroin operation... ever seen in Centre County'Gricar's photo was posted on internet press release trumpeting heroin ring grand jury investigation shortly before his disappearance

Gricar's laptop computer missing, police sayby Bill Keisling

Posted April 17, 2005. Revised April 30, 2005 11:37am -- Another drug prosecutor has vanished under mysterious circumstances in Pennsylvania. Centre County District Attorney Ray Gricar, 59, of Bellefonte, was reported missing on Friday, April 15, 2005, after he failed to return from a drive. His car was later found abandoned on a gravel parking lot of an antiques mall outside of Lewisburg, PA, in Union County, almost fifty miles from State College. Gricar enjoyed unwinding by taking long drives, and shopping for antiques. Police and fellow prosecutors initially said they knew of no motive for foul play.

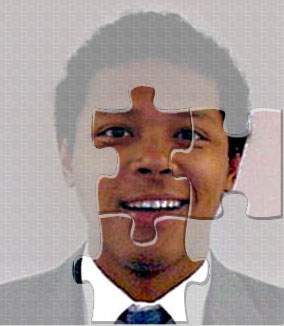

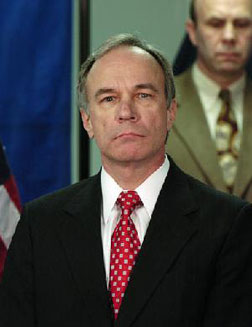

Centre County District Attorney Ray Gricar (top) at a March 31, 2005 press conference announcing the record heroin bust.

Second from top, Gricar stands beside AG Corbett announcing the heroin arrests in the attorney general's press release, published on the net.

In the third photo, Gricar stands beside his red-and-white Mini Cooper, which was found abandoned on a gravel parking lot in rural Pennsylvania, with no sign of Gricar. Gricar's strange disappearance is perhaps the latest in a long series of peculiar endings for prosecutors in Pennsylvania.

Bottom photo shows aerial view of disappearance area, with Susquehanna River on the right. Notice abandoned railroad bridge running across the river. Click here to enlarge aerial photo. Image courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey.

Yet, only days before, Gricar helped announce the prosecution and grand jury investigation of the largest heroin ring in his county's history.

Meanwhile, in what could be a clue, police at an April 21 press conference said they have been unable to locate Gricar's laptop computer, while his cell phone had been left behind in his car. A grand jury had been investigating the drug ring. It's not known what information may have been on the DA's computer.

The missing laptop perhaps provides a motive for a possible abduction of the DA. It seems odd that Gricar would take his laptop from his car, but not take along his cell phone. It also seems unlikely that a man would jump to his death in the Susquehanna River carrying a laptop.

Shortly before his disappearance, Gricar's photograph was posted on the internet in a press release trumpeting the heroin arrests, and the grand jury investigation.

The March 31, 2005 press release from the office of State Attorney General Tom Corbett relates, "'This is the largest heroin operation that we have ever seen in Centre County,' Corbett said, 'feeding a drug trade that stretched throughout the region and allegedly resulted in at least one deadly overdose.'"

"Corbett identified the alleged leader of the drug organization as Taji 'Verbal' Lee, 24, originally from Newark, New Jersey. Lee is currently being held in the Centre County Jail on related drug charges....

"Corbett said narcotics investigators began probing Lee's activities in 2003. At that time, agents had begun getting reports of heroin, crack cocaine and powder cocaine being distributed in Centre County by an individual known as 'Verbal,' who was reportedly transporting large quantities of heroin and cocaine from New Jersey to Centre County....

"On Jan. 11, 2005, Lee was arrested by officers from the Centre County Drug Task Force shortly after he allegedly arranged to deliver 348 bags of heroin to an undercover agent.

"Corbett said that the grand jury also recommended that Lee be charged in connection with a fatal heroin overdose which occurred in State College. The grand jury found that Lee was the source of heroin involved in the Jan. 28, 2004 death of Boyd Francis.

"Lee allegedly delivered 30 packets of heroin to Francis the evening before Francis died. In addition, the grand jury found that Lee instructed associates to destroy the remaining heroin used to supply Francis, after police seized several packets of heroin while investigating the fatal overdose."

An April 1, 2005 article in the State College (Pa.) Collegian, reports,

"Centre County District Attorney Ray Gricar said heroin and cocaine are problems that have been increasing throughout Pennsylvania."'This was investigated by a statewide grand jury and as a result, drug charges being filed,' he said. 'It's a significant victory for combined law enforcement to deal with the drug problem.'

"Gricar said the Centre County Drug Task Force provided the initial information and as the investigation progressed, the Attorney General's Office began to investigate."

Five individuals were arrested, two others had already been detained, and a 25 year old was wanted on fugitive charges. Preliminary hearings were set to begin on April 6, the paper reports, the week before Gricar's disappearance.

The case would be prosecuted by Senior Deputy Attorney General Michael T. Madeira, of Cornett's Drug Strike Force Section, AG Corbett announced.

The Monday following his disappearance, Gricar missed a scheduled hearing for a pending drug case.

Gricar's car was found beside the Street of Shops antique market, on Water Street in Lewisburg, several hundred feet from the Susquehanna River and an abandoned railroad bridge leading across the river. (Click here for an enlarged aerial photo.) Lewisburg is also the home of the Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary and the Allenwood Federal Prison Camp. Gricar was last heard from on Friday, April 15, at about 11:12am, when he called his girlfriend, Patty Fornicola (a clerk in the DA's office) on his cell phone, telling her he was taking a drive along Rt. 192 in the Penns Valley area. The road leads into Lewisburg. Fornicola on April 29, 2005, would say their conversation had been brief, and Gricar had offered no explanation of where he was heading or when he might return. Earlier that morning, Fornicola would say, she and Gracor had gone through their normal morning routine; while she was preparing to go to work, she says, Gricar told her he was taking the day off. She says she left a note for him.

Police say there was no sign of struggle in Gricar's abandoned car. He liked to shop at the antiques mall, we're told.

Police say they found Gricar's cell phone in his car. The phone had been unused since he had called his girlfriend Friday at 11:12am. Reports say Gricar's girlfriend reported him missing that Friday evening at about 11:30pm.

Similarities to Luna case

DA Gricar's disappearance and its attendant press coverage bears striking resemblances to the equally mysterious fate of former Assisant U.S. Attorney Jonathan Luna, who was found dead after an inexplicable car ride in December 2003.

-- At the time of their disappearances, both prosecutors were involved in high-stakes heroin cases.

Bricks and bricks from foreign dudes Up Top.

-- The drug suppliers in both cases were from the New York city area. "Bricks and bricks from foreign dudes up top," as Luna's FBI informant, Warren Grace, explains.

-- Both men disappeared on car rides, while they were alone.

-- Both men vanished without their cell phones. Luna's cell phone was found on his desk, while Gricar's was in his car. This seems to indicate misplaced trust, or perhaps a sudden interruption that called them away from their routine or expected activites.

--Gricar's laptop, police say, is missing. Luna's laptop was found on his desk at work. At the time of Luna's death, Lancaster County, PA, coroner Barry Walp suggested that some of the 36 stab wounds inflicted on Luna's body appeared to have perhaps been intended to make him talk. "You would think they were perhaps after information from the guy when you see something like this," Coroner Walp told a local paper in December 2003. Gricar's disappearance follows on the heels of a widely distributed DVD titled, "Stop Snitching," in which retaliation is promised for those cooperating with drug prosecutions.

-- Both Luna and Gricar seem to have set out, for reasons unknown, perhaps to predetermined, out-of-the-way destinations, as if on a rendezvous with someone they trusted. Phone records apparently offer no clues. Or, both men may have been waylaid by a stalker or stalkers; Luna, driving home, and Gricar, while shopping for antiques.

-- The press coverage of both disappearances also bear striking similarities. Unreliable or illogical sightings may offer false clues. The Centre Daily Times, in an April 20, 2005 article, reports Gricar's car was seen by employees of the Street of Shops antique market between 5 and 6pm on Friday evening, the day of his disappearance. The paper then quotes mall owner Craig Bennett, 48, as telling police investigators he witnessed a man fitting Gricar's description, wearing a blue fleece jacket, waiting in front of an uncompleted mall storefront about noon the following day, Saturday. "It appeared as though he was waiting for seomeone," the CDT quotes Bennett as saying. "It had all the look as if he was waiting for someone." It seems unlikely though that DA Gricar would leave his car overnight in the mall parking lot, not use his cell phone, and not check in when he was already reported missing on Saturday, April 16. Similar supposed sightings in the Luna case later failed to pan out.

-- Both men were subjected to unlikely suicide theories in the press.

Suicide theories floated in Gricar case, and other cases

Gricar's disappearance is the latest in a long series of peculiar endings for prosecutors and prosecutor office employees in Pennsylvania.

Over the years, Pennsylvania law enforcement has had an equally bizarre history of attempting to classify these events as suicides.

In the Gricar case, the AP and the State College daily paper, the Centre Daily Times, have already begun floating suicide theories. Gricar's "late brother, Roy J. Gricar, of West Chester, Ohio, went missing for more than a week in May 1996 before his body was found in the Great Miami River. He was 53, according to the Dayton Daily News," the paper reports. Brother Roy Gricar, the paper relates, told his wife he was taking a walk, was was later found drowned in the river, his death ruled a suicidal drowning.

Three other curious cases where suicide theories were floated come to mind: Jonathan Luna, of course, in 2003; Allegheny County DA Robert Duggan in 1974; state attorney general aide Gaylor Dissinger in 1983. Both Duggan and Dissinger were found shot to death under mysterious circumstances, even as controversies involving organized crime swirled around the offices of the deceased.

"Cops historically in Pennsylvania have floated suicide theories in cases they're unwilling or unable to crack. Particularly a case involving internal agency corruption," I point out in The Midnight Ride of Jonathan Luna. "Suicide offers a convenient explanation that allows an expensive and embarrassed investigatory team to be broken up and sent home. Case closed. It also seeks to reassure people living around the death scene that a murderer isn't on the loose.... There are other benefits, sometimes involving cover-up of mob infiltration (or is that informant misbehavior?)."

In my 1991 book, Maybe Four Steps, I recount the mysterious fates of Duggan and Dissinger.

Pittsburgh DA Robert Duggan

Robert W. Duggan was district attorney of Allegheny County, which includes Pittsburgh, from 1964 until his death in 1974. During Duggan's ten-year tenure as DA there were few prosecutions for gambling. Republican Duggan however was hardly the first or last corrupt Pittsburgh official. Duggan's predecessor in the DA's office was Democrat Edward "Easy Going Eddie" Boyle. Boyle is said to have lost at the polls to Duggan because, during the election campaign, the Republicans under governor William Scranton sent state police on a much-publicized raid of previously untouched Pittsburgh whorehouses, arresting 70 people in vice raids, underscoring just how "easy going" DA Eddie Boyle had been.

Once in office, by most accounts, Duggan picked up where Easy Going Eddie left off. The main difference in both men's public service seems to be that Boyle's career was allowed to end at the polls, while Duggan's was terminated at the hands of a relentless prosecutor -- Richard Thornburgh.

Historically, as in most communities, Pittsburgh's politicians sent around collectors to the bookies and the prostitutes and the purveyors of vice, insisting on a piece of the sin money for the political machines. It's the old protection racket. One observer told me that up into the 1950s, through the mayorship of David Lawrence (who later became governor of Pennsylvania), Pittsburgh's collectors turned the money over to the political parties. But in the 1960s, with the advent of television, the party system began to break down and each politician became a free agent, each having to raise money for, among other things, expensive television commercials. In the old days office holders were selected by party bosses. Television commercials suddenly provided the means of going over the heads of the bosses straight to the public. Television, the herald of democracy the world over, killed the political machines in the United States.

District attorney Duggan used two collectors to raise money -- Robert Butzler, the rackets squad chief at the county detective bureau and, later, Samuel Ferraro, who followed Butzler as rackets squad chief. If you were a gambler and you wanted to avoid trouble with the law you paid the DA's rackets squad chief. If you didn't pay the rackets squad chief he'd arrest you and Duggan would prosecute, though this seldom happened, as the graft system by this time was so entrenched and well practiced.

In Pittsburgh it's widely held that Duggan's undoing wasn't dishonesty, but a falling out he had with wealthy Republican matron Elsie Hillman. She had married Henry Hillman, holder of one of the world's great fortunes, and her contributions and whims could sway the decisions of senators and presidents.

Duggan himself had been born into money, was comfortable among the country club set, controlled a family estate in nearby Ligonier Township, and enjoyed a long-standing relationship with Cordelia Scaife May, an heir to the Mellon fortune.

The precise nature of Duggan's supposed falling out with Hillman remains in dispute. One observer said Duggan wanted his cousin named as US attorney, while Hillman wanted Thornburgh. This dispute, said the observer, caused bad blood. In the end, according to Pittsburgh political lore, Hillman offered Thornburgh the job only after he promised to go after Duggan.The Pollyannas among us suggest that Hillman and the other party bosses ran out of patience with patrician Duggan, who hung out at the club, remained above the fray and refused to do the party bosses' bidding. Some even suggest that Duggan didn't know what his collectors were up to, that he had money of his own and so didn't need graft, that Duggan was an innocent bystander who was persecuted for activities his party had sanctioned for more than one hundred years. Others say Duggan certainly knew what his collectors were up to, that the money they skimmed went into his pocket (or at least was meant to meet campaign expenses, such as television time).

In any event, Thornburgh went after Duggan. What followed was a cat and mouse game between the two prosecutors, a relentless pursuit. Fearing that Thornburgh was about to come after collector Robert Butzler, Duggan moved Butzler out of the way to a police chief's job in the suburbs while shifting the collection duties to Samuel Ferraro. As Thornburgh got closer, Duggan secretly married Cordelia Scaife May, whose wealth, observers say, was meant to mask the unaccountable graft money Duggan had been receiving for years. Thornburgh then subpoenaed records which he said proved Duggan's money was graft, and not May's. Collector Samuel Ferraro then was threatened with prosecution, only to be released after he agreed to cooperate with Thornburgh's investigation. With Ferraro agreeing to talk against Duggan, finally the day came when Duggan was indicted for failing to report income of $137,416 from 1967 through 1970.

Thornburgh's victory was extremely short lived. Within hours of his indictment, on March 5, 1974, Duggan was found shot to death on his family estate in Ligonier, the victim of a shotgun blast. The body was found on the grounds of the estate; somehow the shotgun ended up seven to ten feet from the body. Duggan, authorities said, apparently had been hunting before accidently or purposefully turning the shotgun on himself.

The Pittsburgh Press asked, "Was the law closing in on Robert W. Duggan so inexorably that his only escape was suicide?"

Upon hearing the news of Duggan's death Thornburgh told a reporter, "The terrible personal tragedy overshadows every aspect of this case. Anytime a guy perceives himself to be in a position that he thinks he has to take his own life, it's very sad. I've known tragedy in my own life. I know what it is."

Thornburgh's crocodile tears aside, it's not all that clear that Duggan took his own life. For one thing, how had the shotgun ended up ten feet away from the body? For another, how had Duggan managed to shoot himself with the long-barrelled gun? "You don't shoot yourself with a shotgun with your shoes on," one investigator told me, pointing out that the barrel was so long only a bare toe could have fired the trigger.

Speculation persists that Duggan had been murdered. Who had a motive for killing the indicted DA? Perhaps mafia bookmakers who'd been paying off Duggan over the years feared he'd talk. The suspects could even had included wealthy Pittsburghers, who'd been embarrassed by Duggan. We'll probably never know, as Thornburgh accepted Duggan's death as a suicide and closed the case. There was never a serious investigation of the supposed suicide, though such an investigation may have laid bare a century's practice of organized crime buying political protection.

The point is, Thornburgh obviously wasn't interested in exposing the historical involvement of organized crime in law enforcement. He was obviously only interested in getting Robert Duggan out of the way.

Gaylor Dissinger, aide and campaign treasurer to the state attorney general

In the 1980s, controversies surrounding Pennsylvania Attorney General LeRoy Zimmerman and his connections with bribery scandals and organized crime figures made Zimmerman's campaign contributions the subject of intense scrutiny. The man responsible for Zimmerman's 1980 contribution reports, Attorney Gaylor Dissinger, died under mysterious circumstances.

The death of Gaylor Dissinger became one of the most enduring mysteries of Pennsylvania law enforcement. Dissinger worked for Zimmerman in various capacities, in the DA's office, in the campaign, in the AG's office. Dissinger died on October 18, 1983, at the age of 36. He was found in his bed, shot to death by what one reporter calls "an out-of-state gun." The coroner ruled it a suicide. Yet no note was found, and the police report states, "there was no definite reason known at this time for the deceased to have taken his life."

Among the personal items found at the scene were two tickets to an upcoming Phillies baseball game. One neighbor, Kenneth Dickey, told police he'd last seen Dissinger that morning. Dickey "advised that the deceased had two tickets to the Phillies and had asked him to attend it with him, but that he had to decline." Another neighbor, Mrs. Andrew Leh, said her husband had last seen Dissinger that morning when "they had discussed the Penn State game which was to be played that afternoon." Another neighbor, Jan Peterson, told police she'd last seen Dissinger that morning "working in his yard," after which she's seen Dissinger go "over to the Borough Park to run on the track."

All of which is certainly odd for a man about to kill himself. He gets up, puts in some work in the yard so it looks neat, goes for a jog to keep fit and trim, asks a neighbor to attend a Phillies game with him, watches a football game, and then blows his head off.

The police reported Dissinger had last been seen alive at 3 pm, Saturday October 8, 1983. The body was found the following Tuesday under equally mysterious circumstances, and the coroner ruled "the time of death was anywhere in the last 30 to 40 hours."

The police report, filed by officer Donald L. Tappan, of Camp Hill, PA, reads, "On 11th October, 1983 at approximately 1155 hours, I received a phone call from the office to stop and pick up a message. Upon arrival at the station, officer William Donovan gave me a message that I was to meet Mr. LeRoy Zimmerman at 415 Parkside Road (Dissinger's house—Ed.), in reference to Mr. Zimmerman not being able to make contact with the above mentioned (Dissinger—Ed.) at that location. I went to the location along with chief Andrew C. Janssen and upon our arrival were met by Mr. Pete Kramer. Mr. Kramer advised us to go into the residence that the deceased was upstairs in the bedroom. Upon our arrival to the upstairs bedroom of the deceased, he was found lying on his right side covered with a blanket and some type of terry cloth piece of clothing over his head. A brief inspection of the body by the undersigned showed a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the left side of the head and a .38 cal Smith and Wesson hand gun partially in the victim's right hand. (In the police report the word "right" appears to be retyped over the partially whited-out word "left" hand—Ed.) It appeared that the shot was fired by the victim using the thumb of his right hand (here again the word "right" appears to be retyped over the word "left"—Ed.), in order to pull the trigger of the weapon.... Mr. Kramer advised that he had spoken to the deceased on Saturday 8th October 1983 at approximately late morning hours. He advised that when Mr. Zimmerman could not make contact with him this date he was asked to go to the residence. Upon his arrival there he advised that the front door was locked and he went to the garage door and found that it was not locked. He then went to the back door after going through a screened-in back porch which was unlocked and found that the rear door was in the locked position but when he pushed on same it opened partially. He advised that he had looked for forced entry and found none and went to a neighbor's and called Mr. Zimmerman and after that entered the home via the garage door then through a basement door into a den. He then went to the bedroom and found the deceased lying on the bed. That time was 1150 hours.... Notification of the deceased's mother was made by Mr. Zimmerman and his personnel."

Unnamed "friends and co-workers" at the attorney general's office told police Dissinger had been "in a depressed state of mind for sometime" and so the incident was ruled a suicide. The local police obviously deferred to the opinion of the attorney general's office that it was a suicide. But questions remain. Why was Dissinger working in his yard and jogging if he intended to kill himself later in the day? Why did he ask a neighbor to attend a sporting event with him? Why, if he thought little of the future, was he looking forward to a Penn State game? Why shoot himself in the left side of the head with his right hand, awkwardly crossing his arm before pulling the trigger with his thumb? Why did police expect to meet Zimmerman at the scene? Who covered the head with terry cloth? If the house was unlocked, why wasn't foul play suspected? What was the origin of the gun? With all these questions, why didn't Zimmerman, the state's chief law enforcement officer, push for an investigation of the death of his aide, which he surely could have attained? Who killed Gaylor Dissinger?

Two facts survive: Very serious questions had been raised about Attorney General Zimmerman's election returns; Gaylor Dissinger, the man who signed those election returns, died a mysterious death.