‘Direct removal’ clause eyed for A.G. Kathleen Kane tried once before — and failed

Kane opponents play fast and loose with state constitution, law and history

The state constitution’s direct removal clause wasn’t meant as an easy alternative to impeachment, as Kane’s opponents today say. It was meant to provide a means of removing an office holder incapacitated by illness, not accused of a crime, or occasions not warranting impeachment.

An obscure three-sentence clause in the Pennsylvania constitution has lately but improperly been suggested as a panacea for quickly removing Pennsylvania Attorney General Kathleen Kane from her elective office, without the mess and bother of a legislative impeachment, or a jury trial.

The last, beguiling sentence of the obscure clause, today found in Article VI Section 7 of the state constitution, reads:

“All civil officers elected by the people, except the Governor, the Lieutenant Governor, members of the General Assembly and judges of the courts of record, shall be removed by the Governor for reasonable cause, after due notice and full hearing, on the address of two-thirds of the Senate.”

Pennsylvania officials and their mouthpieces in the media these days are always looking for a quick fix requiring a minimum amount or work, little or no research, and just as little public scrutiny.

So it should come as no surprise they’ve lately latched onto these 48 words like a vampire hunter grips a silver spike and garlic.

The process described in the clause has variously been called a “direct removal,” or “direct address.” It is, on its face, different from an impeachment, which requires lengthy action by both houses of the legislature.

State newspapers recently have misinformed their readers that the “direct removal” clause is both applicable to Kane’s case, and has “never been tried before.”

“With Kane ineligible to practice (law), Gov. Wolf might work with the Senate to apply a never-used ’direct removal’ provision in the Constitution,” reporter Charles Thompson told Patriot-News readers on August 31.

Again, on September 22, Thompson writes, “State Senate lawyers are studying a never-used clause in the state Constitution that could lead to her removal from office.”

“Senators mull over whether to act on removing Kane from office,” writes Jan Murphy, also in the Patriot, by what she calls the “never-used ‘direct removal’ provision.”

Columnist John Baer, in the Philadelphia Daily News, writes, “(I)f the high court suspends Kane’s law license, that would add to the gravity of moving forward” with the direct removal process. Baer adds, “Such movement would be unprecedented.”

“State Attorney General Kathleen G. Kane’s legal jeopardy has put the spotlight on a never-used provision in the state Constitution for directly removing elected officials from office,” writes Robert Swift of the Scranton Times-Tribune.

These reporters go on to say that lawyers in the state senate and the governor’s office were busy “researching” the process of a speedy direct removal of Kane.

Trouble is, they’re all wrong.

The “direct removal” process was tried before, and it was unsuccessful. And it was unsuccessful for reasons that directly bear on Kane’s case.

That state lawyers and the reporters don’t know about the history of this constitutional failure speaks volumes.

As I read suggestions that the direct removal process be applied against AG Kane, a few thoughts naturally crossed my mind.

What exactly does this obscure sentence in the state constitution mean? What is this provision for? Has it been used before, and to what effect? What was the intent of the framers to include this in the constitution?

To find out about all this, I had to do something newspaper reporters and government lawyers apparently are loath to do these days: I had to open a book and read some history.

It turns out the clause in question was added to the state constitution in its 1874 revision. (It’s not present in the 1838 draft.)

When the direct removal clause was only seventeen years old, in 1891, a Pennsylvania governor attempted to misuse it to remove two state row officers at a time of “political excitement.” Not much different than Kane’s case, it turns out.

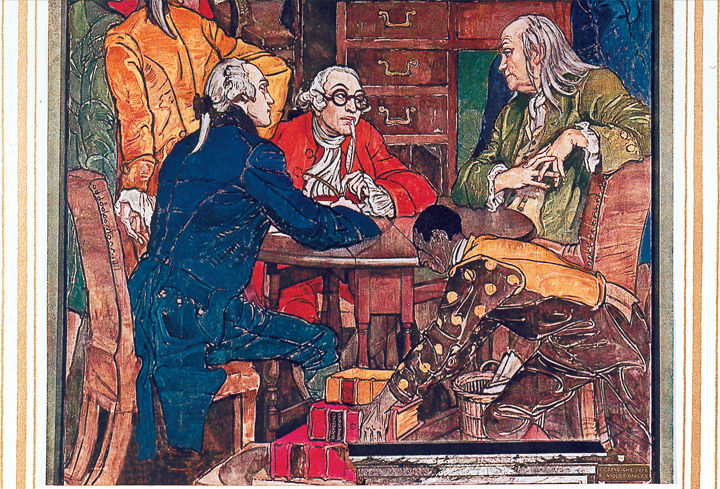

As recorded in the Proceedings of the Pennsylvania State Senate, Gov. Robert Pattison convened an Extraordinary Session of the senate in October 1891, to remove from office state Treasurer Henry Boyer and Auditor General Thomas McCamant by the direct address provision.

Gov. Robert Pattison: tried direct removal, and failed |

|

The two were accused of taking bribes from the treasurer of Philadelphia, who himself was accused of embezzling “an amount in excess of a million dollars.”

In his book Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States (Boston Book Company, 1895), Roger Foster writes that, “The counsel for all the officers objected to the jurisdiction of the senate upon the grounds that the governor had no power to institute charges, that the proceedings upon such charges were not ‘executive business,’ and consequently could not be considered at an extraordinary session of the senate, and that no officer could be removed for an impeachable offense without a previous conviction upon an impeachment or indictment.”

The problem then is the same as the problem now, should this “direct removal” clause be contemplated against Kane.

Two other clauses in the constitution directly address removal of state officials from their elective offices: the Impeachment Clause (Article VI Sections 4-6); and the first sentence of Section 7.

Both of these sections contemplate conviction by a jury trial.

The impeachment clause reads, “The person accused, whether convicted or acquitted, shall nevertheless be liable to indictment, trial, judgment and punishment according to law.”

The first sentence of Section 7, Removal of Civil Officers, the preamble to the direct removal clause, reads, “All civil officers shall hold their offices on the condition that they behave themselves well while in office, and shall be removed on conviction of misbehavior in office or of any infamous crime.”

So what happened in 1891, when the governor attempted to remove the state treasurer and auditor general by the direct removal clause, without a jury trial?

Pretty much what would happen today.

In 1891, both the state treasurer and auditor general took the stand in the senate and proclaimed voters had duly elected them.

Both pointed out that neither had been convicted of a crime at trial.

Auditor General McCamant laid out his case, which surely would be echoed by AG Kane today:

• That the governor “had no authority under the constitution and laws of this commonwealth” to seek his removal by means of direct address.

• That he had been “lawfully elected by the people of this commonwealth to said office.”

• That he had been “duly, rightfully and lawfully exercising and performing the duties of said office.”• And that, “I expressly deny each and every charge of official misbehavior.”

Auditor General McCamant, moreover, like the treasurer, pointed out that he had a constitutional right, the same as all citizens, to a fair jury trial before guilt can be affixed.

McCamant told the senate, “it is proposed to virtually try me, in this form of proceeding, on criminal charges of alleged misdemeanors in office, in direct violation of the law of the land, without a fair trial by an impartial jury of my vicinage, but before a tribunal not bound by oath or affirmation, which is governed by no legal rules of evidence, and which is essentially a political tribunal called together by the Governor in a time of great political excitement, for the purpose of condemning me, and this when the supreme law of the land provides two certain, ample and clearly constitutional methods for removing me from office if the truth of these charges can be proven against me.”

McCamant pointed out that an impeachment proceeding must begin in the state general assembly, not the senate, and so this was not a lawful impeachment trial.

The only other means to remove him, he said, was the sentence before the direct removal clause, which reads:

“All officers shall hold their offices on the condition that they behave themselves well while in office, and shall be removed on conviction of misdemeanor in office or of any infamous crime.”

“I am advised,” McCamant told the senate, “that this clause refers only to a conviction in a court of law, before a jury regularly summoned and sworn, upon an indictment duly found, and in a regular trial according to law, and not to a conviction before the Senate sitting as a court of impeachment to try articles of impeachment duly presented by the House of Representatives, or to a proceeding like the present one.”

So what was the meaning of the direct removal clause, which today, more than a century later, also threatens Kathleen Kane? More than a century ago, McCamant provided the explanation:

He says, “The last clause of section four of said article provides that, ‘all officers elected by the people, except Governor, Lieutenant Governor, members of the general assembly and judges of the courts of record learned in the law, shall be removed by the Governor for reasonable cause, after due notice and full hearing, on the address of two-thirds of the Senate.’ I am advised that the ‘reasonable cause’ for which an elected officer can be removed in this manner under this provision, does not refer to or include a cause amounting to an impeachable or indictable offense, but refers only to causes other than impeachable or indictable offenses, incapacitating him from properly discharging his duties, such as insanity, senility, incompetency, protracted illness or absence, or other similar cause, which would not be sufficient to warrant either his impeachment or indictment, and in any of which cases there would be no mode of removal possible, except for this provision.” (Emphasis mine.)

Simply put, the direct removal clause wasn’t meant as an easy alternative to impeachment, as Kane’s opponents today say. It was meant to provide a means of removing an office holder incapacitated by illness, and not accused of a crime, or an impeachable offense.

By using the direct removal clause against Kane, her opponents would be recognizing that she has not committed an impeachable offense.

In 1891, by a party vote of 28 yeas to 19 nays, the senate denied the governor’s request for removal of the state treasurer and auditor general by direct address.

In a proclamation sent to the governor, the senate wrote, “Resolved, That as the said charges preferred by the Governor in manner aforesaid against said officers, are charges of misdemeanor in office, for which said officers could be proceeded against, both by impeachment and by indictment, and if convicted thereof, in either of said ways, could be removed; the Senate has no jurisdiction, under Section 4 of Article VI of the Constitution in this proceeding, to inquire into, hear and determine said charges of official misconduct, and to address the Governor asking for the removal of said officers by reason thereof, and thereby to deprive said officers of the right to trial by jury, guaranteed to them under Article I, or to a trial in regular proceedings by impeachment in accordance with Sections 1, 2, and 3, of Article VI of the Constitution.”

With Attorney General Kathleen Kane we’d likely see the same outcome to a direct address removal attempt today.

I reached out for comments from spokesmen for Gov. Tom Wolf, and senate President Pro Tempore Joseph Scarnati. Both offices have been cited in the press as actively investigating whether Kane could be removed from office by the direct address provision.

Neither official’s spokesman was immediately available for comment.An aide in Gov. Wolf’s press office conveyed her understanding that the proposed direct removal clause “had never been used” before in Pennsylvania history.

- Bill Keisling

posted September 24, 2015